The COVID pandemic is an all too recent memory for us, but this is only the latest in a long history of major outbreaks of disease.

Here is a perspective of pandemics written at the height of COVID, and below that is an article about the mercifully small outbreak of bubonic plague in Suffolk in the early 20th Century.

January 2025

History and Pandemics

From FRAM Newsletter No. 2, September 2020 p4.

Alison Bowman

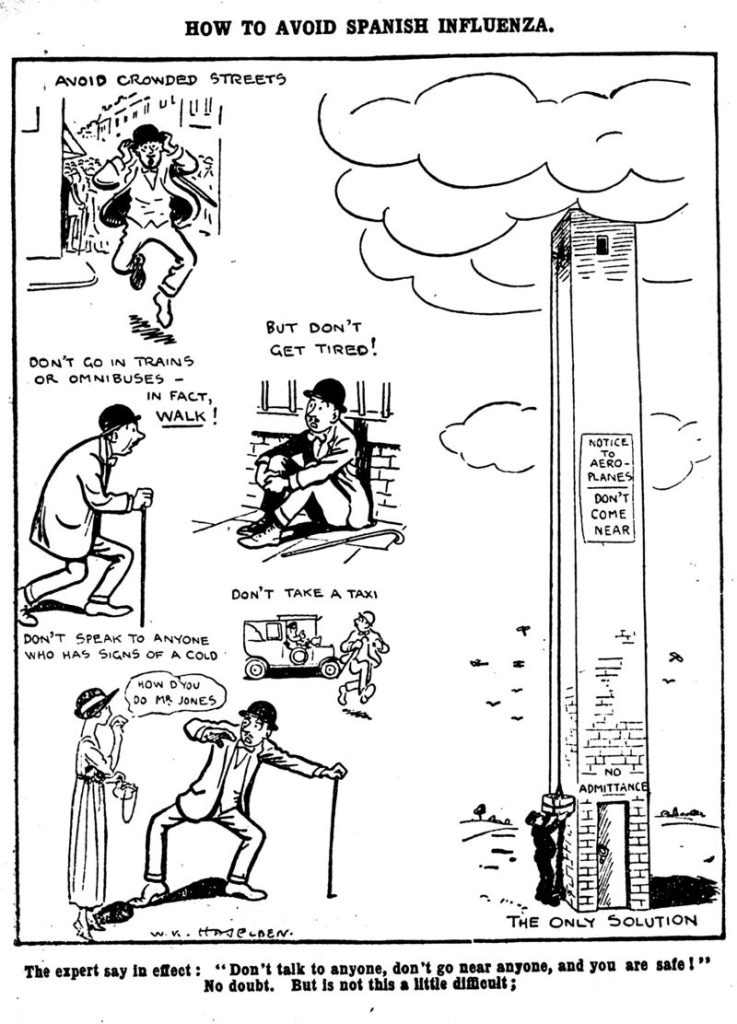

over public health messages (look familiar?)

When does history start? It is a question that has vexed many historians and curators. We are fortunate in Framlingham in that Harold Lanman collected the ephemera that most people consign to the rubbish bin. What will be remembered in 100 years from now as we save little and the amount potentially collectable is vast? John Bridges pointed out that the minutes of the parish meetings in the Great War make no mention of the war. In all likelihood it was so present in everybody’s minds that they felt no need to record it. Will it be the same for the extraordinary year we have been experiencing? COVID 19 is so much with us in all aspects of our lives that we may not properly record it and experiences will be taken for granted. Schools were closed and meetings, sports events and large social gatherings are cancelled.

Of course pandemics are not new. Black Death and Spanish flu (which did not come from Spain) comes to mind as well as later outbreaks such as SARS. However beyond this there are few similarities between COVID 19 and Spanish flu (H1N1) other than they both seem to have resulted from animal to human transfer. Despite a degree of public confusion, COVID is not a flu virus and the range of those most affected is very different. Spanish flu was most destructive to the group of otherwise heathy young adults ranged between 15 and 34 years old whereas we know only too well that COVID 19 is primarily fatal to the elderly often with other health difficulties. We do not know yet what the final death toll will be from COVID but it is currently running at 818,000 globally (25th August 2020) with the total deaths from Spanish flu is estimated at 50 million. There is obviously a huge difference in the death toll but like Spanish flu at this time there is no preventative vaccine although we do have many other medical advantages such as antibiotics for subsidiary infections

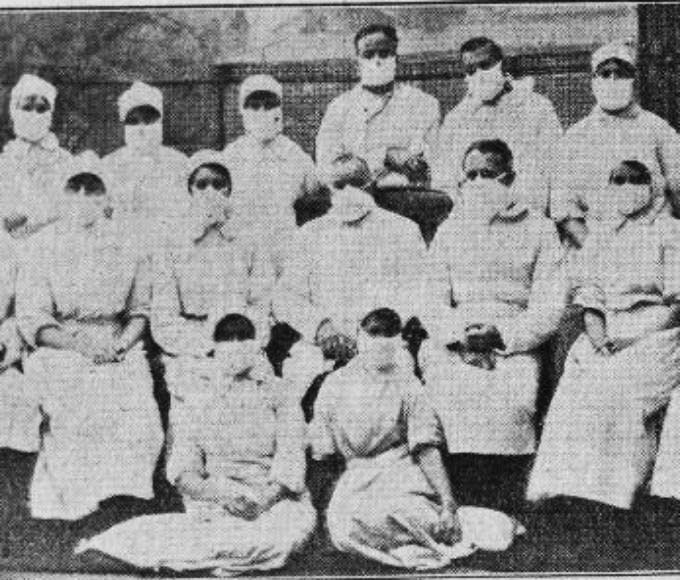

for a photograph, 1919 (source RCN)

Reactions were in many ways similar in that schools were closed, people wore masks and mass hospitals were opened but lack of knowledge of what Spanish flu and how it was spread did not lead to the cessation of gatherings (an error repeated at the beginning of this pandemic) and it ran like wildfire through the population.

I have tried to find comparable figures either at local, county or regional level but this has proved impossible as the ONS only publishes death tolls by region with no granularity, for the East of England it sadly amounts to 4,123 people. The figure for deaths from Spanish flu in Suffolk is estimated to be in the region of 975. At the national level 41,233 have died of COVID and the comparable figure for Spanish flu is estimated at 250,000. As can be seen Spanish flu was far worse than the current pandemic and that it would appear that our area has suffered less than some others in both cases. This may be attributed to a number of different factors such a low population density, a relatively low number of commuters (of which 70% use cars rather than public transport) and a preponderance of older people who may be less inclined to meet in large groups.

The future will become the past and a matter of history but how the final story will pan out… we will just have to wait and see!

Plague in East Suffolk 1906-18

Abridged from two articles in FRAM Journal, Series 3 No. 10, August 2000, p7 and p13.

J & D Black and M V Roberts

There were no cases in Framlingham, but the outbreak was clearly of great concern, and various precautionary measures were taken, described below.

An information sheet in a church in the Shotley peninsula drew our attention to an outbreak of plague in the area in 1910. This episode is not mentioned in the standard texts on the subject. The information in this paper has been obtained from a Report to the Local Government Board in 191111, an article in the Journal of Hygiene in 19142, and an article by David van Zwanenberg, “The Last Epidemic of Plague in England?, Suffolk 1906-1918”3, published in 1970.

The history of plague

There have been a number of pandemics (a pandemic is a prolonged outbreak usually involving a wide area). The earliest recorded pandemic was the Justinian Plague of AD 542-750. The Black Death started in the middle of the fourteenth century and continued until the middle of the seventeenth century. The Great Plague of London (1665-1666) killed 60,000 people out of a population of 450,000. The plague was not confined to London: between July and October 1666,111 people died from the disease in Framlingham (in 1674 the population was eight hundred and sixty)4. After the Great Plague, Britain remained free of plague until a small epidemic occurred in Glasgow in 1900, with 36 cases and 16 deaths.

The last pandemic started in China in 1894 and lasted until the 1930s, killing over a million people in India. India continues to be a centre for endemic plague (an endemic is a continuing state of sporadic cases or minor outbreaks lasting for many years). One of us (JB) saw two cases in India in 1944.

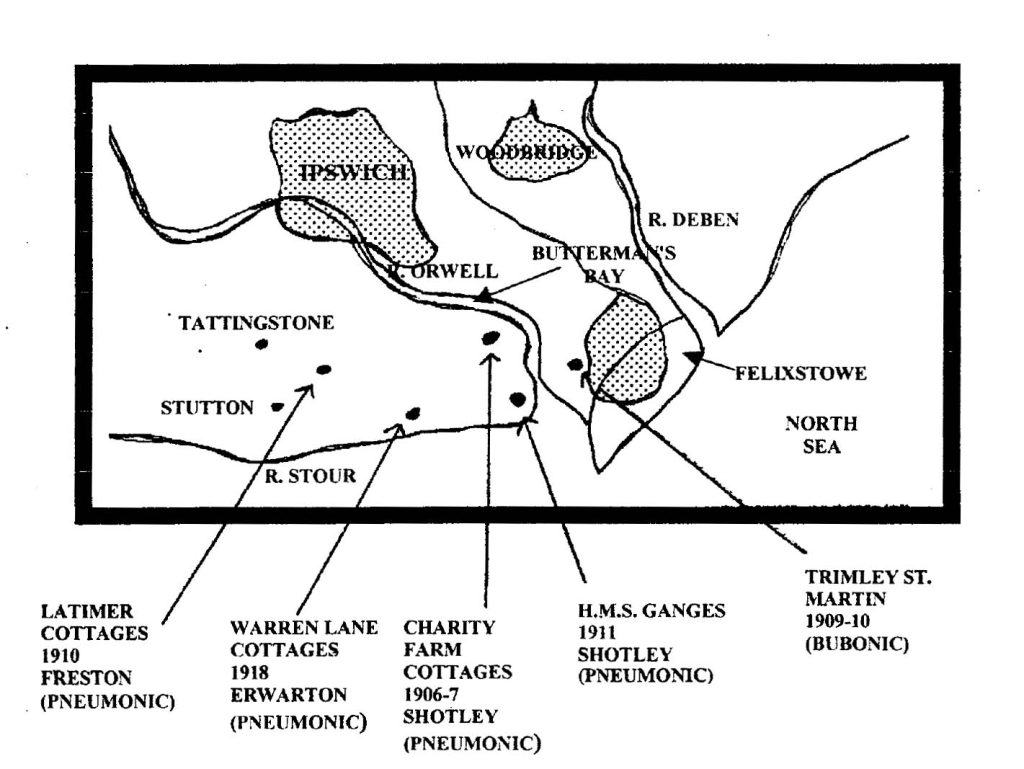

The outbreak in East Suffolk in September 1910

Five miles from Ipswich, between the villages of Freston and Holbrook, are two attached cottages, Latimer Cottages. At the time of the outbreak, Mr. C lived in one of the cottages with his wife and her four children from a previous marriage. On September 13th, AG, a girl aged nine years, became ill with a severe cough, pneumonia, and diarrhoea and vomiting. She died three days later. Six days after her daughter’s death, Mrs. C became ill and died after two days’ illness. Three days after his wife’s death, Mr. C and Mrs. P, a neighbour who had nursed Mrs. C, became ill and died three days later. All the victims had similar symptoms. Dr. Carey, their general practitioner, attended all the patients and Called in Dr. Brown, a physician from Ipswich, to see Mrs. C, but she had died before he arrived. When Mr. C and Mrs. P became ill, the possibility of pneumonic plague was considered, and blood was taken from Mr. C and some bloodstained fluid was removed from Mrs. P’s lung. The specimens were examined by Dr. Llewellyn Heath, the bacteriologist at Ipswich, who grew the plague bacillus from both specimens. Dr. Heath took his material to Professor Sims Woodhead in Cambridge, who confirmed the diagnosis of plague.

The last two patients were buried on September 30th, the vicar taking the whole service in the open air; all those attending had their clothes disinfected. There were no post-mortems or inquests. On October 1st, the contacts were removed to isolation accommodation in Tattingstone Workhouse, which had been opened for this purpose. On the same day, Dr. Sleigh, the Medical Officer of Health for the district, notified the Local Government Board of the diagnosis. All four deaths were thought to be due to pneumonic plague, because of the short incubation period, the high mortality, and the probability of case to case infection. There was no indication how the first victim, AG, had become infected.

Action taken after the Freston outbreak

On October 3rd, the Local Government Board Inspector, Dr. Timbrell Bulstrode, telegraphed Dr. Sleigh that he would visit the area on the following day. His investigations discovered that a number of rats, hares, ferrets, cats and other animals caught near Freston were found to be infected with plague. Handbills were distributed to the public warning people not to touch dead animals.

Outbreaks before and after the deaths in Freston

Two later outbreaks occurred in Shotley (1906-7) and Trimley (1909-10), each involving one or two families. A further case occurred in 1911 at HMS Ganges in Shotley.

How did the plague reach Suffolk?

No conclusive evidence was found about how the plague arrived. There is no evidence that the plague was present in Suffolk before 1906. It is possible that the plague arrived on shipping on the River Orwell, possible via rats on shipping. There is some evidence of infection in rats before the first case in humans. It is also conceivable that the plage arrived in fleas in grain.

Impact in Framlingham

Although there are no records of plague cases in Framlingham and its surrounding area at the time of the outbreak described above, we can be sure that the disease would have had a presence in the mind of any person living in the town who read its local newspaper and witnessed, or actioned, the measures that were taken to eradicate potential carriers of the pestilence. Articles in the Framlingham Weekly News made many mentions. In 1910 and 1911 there were at least a dozen articles about the matter, including measures to irradicate rats.

While these articles demonstrate a very sensible concern on the part of the elders of the town, of the district, and of the county, at what might have become a significant problem, there seems to be surprisingly little evidence of major disquiet on the part of the authorities, or panic among the local population. In recent years, reactions to “new” and life-threatening diseases may have been more immediate and pronounced; but perhaps the contrast in attitudes that this reflects would more appropriately be considered by the sociologist or the media analyst, rather than by the local historian.

Footnotes

- H. T. Bulstrode, Report on suspected pneumonic and bubonic plague in East Suffolk and Essex. (London, HMSO,1911). Reports to the Local Government Board on public health and medical subjects. New series no. 52. ↩︎

- A. Eastwood and F. Griffith, “Report to the Local Government Board on an enquiry into rat plague in East Anglia during the period July to October 1911”. Journal of Hygiene (1914) 14 pp. 285-315. ↩︎

- D. van Zwanenberg, “The Last epidemic of plague in England? Suffolk 1906 – 1918” Medical History, (1970) 14 pp. 63-74. ↩︎

- M. L. Kiivert, A History of Framlingham, (Ipswich, Bolton and Price,1995) p. 18. ↩︎