Simon Garrett

Sir Robert Hitcham, 1572 to 1636, was not born in Framlingham – he was born in Levington – and his connection to Framlingham started only in 1635, a year before his death. But as a major benefactor to the town, his influence on the town lives on to the present day.

Robert was born of lowly origin in Levington, near Ipswich. His father and grandfather had a business cutting and selling heather which was used for the making of brooms. Robert was educated at the Free School at Ipswich and later Pembroke Hall (now Pembroke College), Cambridge, studying law. He was admitted to Gray’s Inn on 3 November 1589 from Barnard’s Inn and was called to the Bar in 1595.

He became a Member of Parliament for West Looe, Cornwall from 1597 to 1598; for King’s Lynn, Norfolk from 1604 to 1611; for Cambridge in 1614 and for Orford, Suffolk from 1624 to 1626.

He was knighted on 29 June 1604 by King James I. Hitcham held a number of posts including: Attorney-General to Anne of Denmark, Queen Consort to James I (1603–1614); Sergeant-at-law (1614); and King’s Senior Sergeant-at-law (1616). He acted as a Judge of Assize on several occasions.

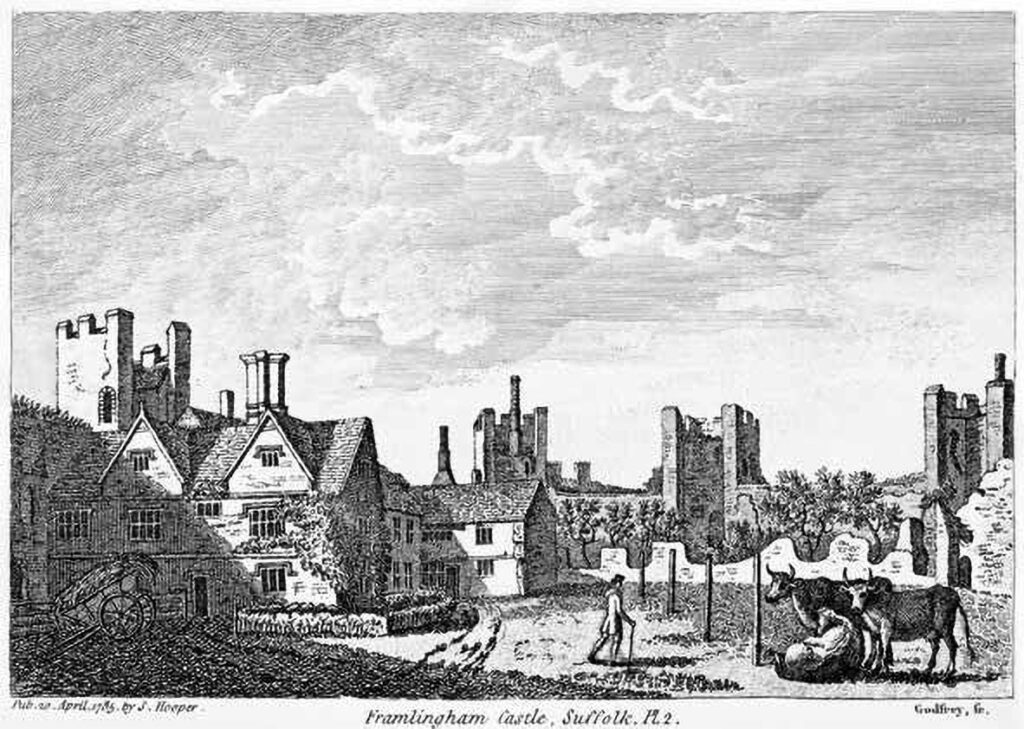

In 1631, Hitcham bought Seckford House, Ipswich (from the Seckford family), and probably lived there from that time. His connection with Framlingham started on 14th May 1635, when he purchased Framlingham Castle, together with the manors of Framlingham and Saxtead, from the bankrupt Theophilus Howard, 2nd Earl of Suffolk, for the sum of £14,000.

Less than a year later he died on 15th August 1636 and now lies in a tomb in the Church of St Michael the Archangel, Framlingham.

According to an inscription on Hitcham’s tomb, in the south chapel of Framlingham church, he was:

‘Attorney to Queen Anne in ye first yeare of King James, then knighted. And afterward made ye Kings senior Serjeant at Lawe and often Judge of Assize’.

A year after the purchase of Framlingham Castle, and a week before his death in August 1636, Hitcham drew up his will. He was unmarried and had no offspring: his nephew, Robert Butts, inherited Levington manor, which Hitcham had acquired in 1609, while his sister was given a farm named Watkins. Having provided for the Butts family, Hitcham left his Framlingham estate to Pembroke Hall, to be governed by a trust, on condition that the college set up and maintain a number of charitable institutions for the poor. These were almshouses in Framlingham and Levington, and a school and a workhouse in Framlingham.

The school and workhouse in Framlingham were intended for the benefit of the ‘poore and most needy & impotent’ of three parishes – Framlingham and Debenham in Suffolk and Coggeshall in Essex – and provision was made of ‘a substantial stocke to sett them on worke and to allow to such needy persons of them soe much as they shall farther think fit’. In addition, Hitcham left money for the appointment of a schoolmaster and granted Framlingham church an endowment of £20 per annum for the reading of prayers twice daily.

In order to build the new structures in Framlingham, Hitcham ordered that ‘all the Castle Saveing the stone building’ – that is, the north range, containing the Great Chamber (see below) – was to be demolished, and the materials sold or reused.

The implementation of Hitcham’s wishes was delayed by legal disputes between his executors, the churchwardens of Framlingham and the Pembroke Trustees concerning the receipt of rentals, an issue settled in 1644. By then England was in turmoil. At Pembroke Hall, the Master, Benjamin Lany (in post 1630-44; reinstated 1660-62), and the remaining Fellows were expelled. In the same year, money was ordered to be paid to the new Master, Richard Vines (in post 1644-50), who then ‘employed Workemen, provided Brick & other materialls to erect a Scholehouse, Workehouse, & Almeshouse at Framlingham’. However, work did not progress as planned: Vines sold the materials, refused to undertake the work, and was removed from the mastership. The money he owed was subsequently paid to his successor at Pembroke, Sidrach Simpson, but legal battles were still underway at the time of Simpson’s death in 1655.

One of these legal challenges was posed in 1651 by the parishes of Debenham and Coggeshall, and the complaint was circulated in the form of an ordinance issued by the Lord Protector in 1654. The parishes objected to the terms of Hitcham’s will, arguing that ‘great inconveniences’ would be caused by the poor having to travel to the school and workhouse at Framlingham – a distance of eight miles from Debenham and 45 miles from Coggeshall. Certainly, it was not usually the case that the poor of one parish would have to travel to another to work or be educated, and the churchwardens and overseers of Debenham and Coggeshall would have incurred a great deal of extra cost and trouble if they sent their paupers to Framlingham; Hitcham’s will did not explicitly cover travel costs. The cost of maintenance and accommodation was another concern, and the dispute makes it absolutely clear that Framlingham workhouse was conceived as a non-residential institution, ‘the Will not providing for the Poors habitation nor making any other provisions for their livelyhoods there’.

It was further argued that Framlingham would be inconvenienced by so many poor congregating and residing in the town, and that the poor of the different parishes would find it difficult to work together under one roof:

And in respect of Continual differences, which in all likelihood will arise betwixt the Towns touching their poor, in such sort confused and mingled together, besides the jars and contentions amongst the poor themselves (incident to such sort of peoples) working together under the same roof, whereby the Town of Framlingham will be much disquieted, the work hindered, and more materials in danger to be spoiled and imbezilled than work done.

As a result of the ordinance of March 1653/4, it was agreed that Debenham and Coggeshall would receive a portion of the revenue of Hitcham’s estate to provide for the work and education of their own poor inhabitants, and that the workhouse and school in Framlingham would serve that parish only. This was apparently confirmed by a deed issued by Pembroke Hall in August 1666.

The agreement of 1653/4 allowed the stipulations of the will to be fulfilled. Within a year, Pembroke Hall had built a row of 12 almshouses in New Road, Framlingham; these are dated 1654, and are now listed Grade II*. The contract for the building was drawn up between Pembroke Hall and the Framlingham bricklayers Robert Goodwin, Robert Atkin, John Goodwin and William Spink, ‘according to a plot already drawn and agreed on by Peter Mills of London surveyor’.

Peter Mills (1598-1670) was an important architect, responsible for Thorpe Hall outside Peterborough (1653-56). He also designed the Hitcham Building (1659-61) on the south side of Ivy Court at Pembroke Hall in Cambridge, and may have had a hand in the design of the Red House in c.1664.

Mills is known to have remained active almost until his death: he was one of the four surveyors appointed to supervise rebuilding after the Great Fire of London in 1666 (alongside Christopher Wren, Hugh May and Roger Pratt), and he designed buildings at Christ’s Hospital in London in 1667-68.

Also in fulfilment of Hitcham’s will, in 1653 Zaccheus Leverland was appointed schoolmaster in Framlingham, a post he retained until 1673, four years before his death. Originally, he seems to have taught children (almost certainly boys only) in the guildhall on Market Hill.17 By 1663, Leverland is known to have lived in the north (or Great Chamber) range of the castle, which also contained the schoolroom. Additionally, two pairs of almshouses – forming identical parallel ranges – were built in Bridge Road, Levington (listed Grade II). They display a stone plaque bearing Hitcham’s arms (gules, on a chief or, three torteauxs [sic]). Although these buildings are usually dated to 1654, there is evidence to show that they were erected in 1677. On 28 April of that year, the Steward of Framlingham Richard Porter wrote to Pembroke Hall to inform them of the ‘good forwardnesse’ of the construction work, and also to let them know he had made some alteration to the form of the building. In a letter of July 1677, Porter reported that ‘the Almeshowses att levyngton are finished’ and that he had paid £200 ‘towards the building of them’.

According to the same letter, the next building to be undertaken by Hitcham’s Estate was the ‘Crosse’ at Framlingham, the building in the Market Place which housed Hitcham’s school from 1722 until its demolition in 1788. It is likely that a wider consideration of the subject at the time (see below) led to the conclusion that it was no longer appropriate for the school to be co-located with the workhouse. Probably, this new school was just for boys, with the girls continuing to receive a more ad-hoc education, as appropriate, from the governess of the workhouse. The Market Cross was described in 1787 as: ‘a very Large Building containing a Chamber for Receiving the Stall Stuff another for a School Room and an Open Part Supported by Pillars with Several Shops about it.’

The various schools, almshouses and other recipients of Robert Hitcham’s legacy still live on, and a number of charities bearing his name still survive.

For more information about how the Castle was used as a result of Robert Hitcham’s legacy, see here.

Sources

- “The Red House Part 2”, Emily Cole & Kathryn Morrison, Journal of the Framlingham History Society, Series 7 No. 6 April 2018

- “Education in Framlingham”, Terry Gilder, Journal of the Framlingham History Society, Series 7 No. 6 April 2018

- “Robert Hitcham”, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Hitcham

- “Robert Hitcham”, Coggeshall Museum, https://coggeshallmuseum.org/robert-hitcham/

For Journals of the Framlingham History Society see https://framlinghamhistory.uk/newsletters-and-journals/.