This article first published in the FRAM Journal1.

By Terry Gilder, April 2007

Some additions by Simon Garrett, April 2025

The story of Nicholas Danforth’s family and their departure to New England in 1634 gave Framlingham its strong link to the United States of America, but it was something else, as well. It was another instance of where life in Framlingham became involved in a national movement which was having a profound effect on the Church, and people’s lives generally.

For more information on Nicholas Danforth, see for example the Library of Congress entry2.

There is ample evidence to suggest that Nicholas Danforth was a Puritan. This is the best explanation for his decision to go to America, but it also gives us an additional illustration of how Framlingham reacted to this powerful religious fashion of the seventeenth century. There are several indications that Nicholas must have had strong tendencies towards Puritan belief. Some of these are revealed in the story of the Danforths in New England, but others became apparent before they left these shores. The history of the family, both in America but also in England, has indeed been best chronicled on the other side of the Atlantic, mainly by historians of the eighteenth and the twentieth centuries.

These historians were Cotton Mather (1663-1728) and John Merriam (1862-1959).

Cotton Mather was a determined Calvinist Puritan. Son of a Congregational minister, he graduated from Harvard College at the age of fifteen. Aged twenty-five, he became minister of the North or Second Church of Boston, Massachusetts, remaining in that post for the rest of his life. The church had the largest congregation in New England. But he was more. He was a prolific writer. In an age when contact with England was still considerable, he acquired in 1710 the degree of D.D. from Glasgow University, and in 1713 was made a Fellow of the Royal Society. Mather’s views were strict, and he resisted the liberal trends that developed in American Church life. He was very disappointed to be passed over for the Presidency of Harvard as it became more liberal, and his later life was clouded with rejections and disappointments.

However, in his writings he charted clearly the development of religious life in America. Obviously he stood personally in the mainstream of the Puritan belief which was the story of how New England began. In his book Magnalia Christi Americana: or Ecclesiastical History of New England, from its first planting in the year 1620 unto the year of Our Lord, 1698, first published in England in 1702, he tells the story of how Nicholas Danforth made the decision to join the movement. In 1620 the Pilgrim Fathers had settled in Plymouth, fifty miles down the coast from Boston, where in 1630 John Winthrop arrived to become the first Governor of Massachusetts. Although only one Suffolk person was a member of the Pilgrim Fathers group, it was with Winthrop that an exodus of persons from this county began. Winthrop left from the village of Groton near Sudbury where today, in the Church, and nearby, are monuments to his family and their connection with New England.

Mather would have had authoritative sources for his account of the Danforth emigration. Nicholas himself had died, but his children were still alive. One can therefore assume that Mather spoke to Thomas, the son on whose land Framingham came to be built, and also to Samuel, the second-oldest son. Thomas was the public-figure son, who bought the land upon which Framingham came to develop. He did not live in Framingham, but in Newtown, or Cambridge as it became. This is where Harvard College (of which Thomas was the first Treasurer) developed into Harvard University. Samuel, the son “dedicated unto the prophets” by his mother, before the family left for America, went to Harvard as a student, and became the pastor of Roxbury, New England, 1650-1674. Mather may well have met and spoken with the other Danforth children too. To appreciate Mather’s interpretation of the part that Nicholas played, and its interesting reflection upon life here in England and, in particular, Framlingham, at this time, it is best to turn to the writings of John Merriam in the twentieth Century.

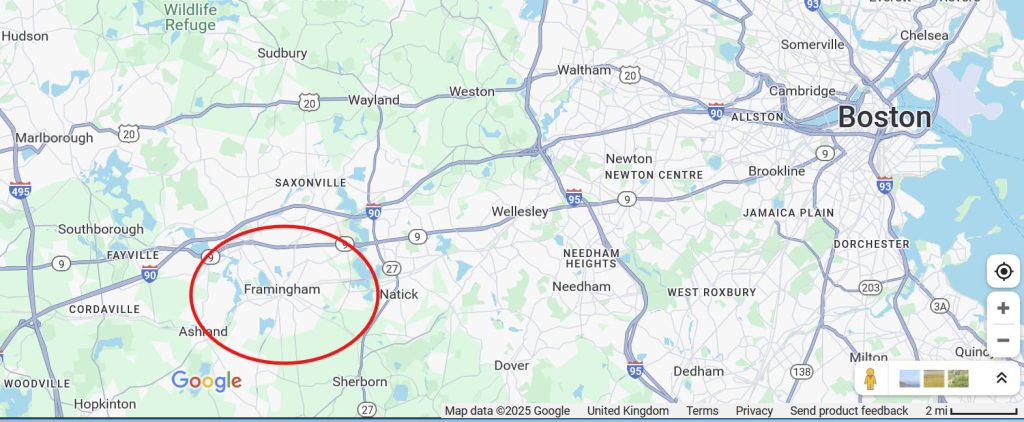

Click the image for a larger view. (c) Google 2025

John Merriam was one of the most prominent Framingham citizens of the twentieth century. By career he was a lawyer, but he was involved in many good causes in the life of the community of Framingham. He took a particular interest in the history of the link between two communities. Not only did he come to our own Framlingham on the occasion of the 1931 Pageant, where he was welcomed and feted with great honour, but he wrote several pieces on the connection3. It was in his introductory piece to the booklet written by our own John Booth Nicholas Danforth and his Neighbours , that he refers to Mather on the Danforths, Explaining the background to Nicholas’s decision to emigrate4. This article can do no better than quote verbatim what Merriam (and Mather) wrote5.

It is thought he [i..e. Nicholas Danforth] came on the Griffin which arrived in Boston September 18, 1634. This was a boat of some 300 tons and the record is that she brought “about 100 passengers and cattle for the plantations”. Think of the discomfort and perils of such a trip. A recent writer, Charles Edward Banks, in his “The Planters of the Commonwealth”, which contains a list of the boats sailing across the Atlantic in the decade of the Puritan emigration, 1630-1640, with partial lists of passengers, describes the herding together of passengers and cargo as follows:

“As far as known no one has left a contemporary description of the conditions of Atlantic travel at that time, and the best that can be done to reconstruct them is by utilizing fragmentary references of emigrants to produce a synthetic picture of an average voyage. The officers’ quarters on the poop deck and the sailors’ bunks in the forecastle were always limited in space, and the only possible place for passengers was the space between the towering stem structure and the forecastle or between decks. Below this was the hold, which was used for the cargo, the ordnance, and the stowing of the long boats. In this part of the ship, as we learn from Winthrop’s story of the Arabella, cabins had been constructed, probably rough compartments of boards for women and children, while hammocks for the men were swung from every available point of vantage”. He adds:

“It may be left to speculation how the sanitary needs of the passengers were provided for in ordinary weather with smooth seas. The imagination is beggared to know how the requirements of nature were met in prolonged storm in these small boats when men, women and children were kept under the hatches for safety. This may be mentioned as an inevitable accompaniment of emigration in its beginning”.

Under the best of circumstances such a voyage was not an inviting prospect to any father with a motherless brood of children.

John Joseph May in his Danforth genealogy refers very pleasantly to Elizabeth, the wife of Nicholas, who died in Framlingham, stating that there was a tradition in the family that she was the daughter of William Symmes, a minister of Canterbury. If so, she was the sister of Rev. Zachariah Symmes, the long time minister of Charlestown. It is interesting in connection with this to learn from Banks that this minister and his wife and six children were passengers in the Griffin, and this fact may naturally have been a potent reason why Danforth came on this particular boat. Other passengers were the Rev. John Lothrop and family, later the minister of Scituate, and William and Anne Hutchinson, and family. As we read of this religious leader, Anne Hutchinson, who soon proved so disturbing in the New England theocracy that she suffered banishment, we wonder if the weather proved sufficiently tranquil to permit discussion between her and her fellow clerical passengers and if so whether or not the layman Danforth joined them. It is also interesting to note that in these four families there seem to have been twenty-four children, six I.othrops, seven Hutchinsons, five Symmeses and six Danforths.

In the face of all these deterrents, what was there to induce Nicholas Danforth in 1634 to say in effect: Nevertheless, God helping me, I propose to cast my lot and the lot of these, my children, and their children to remote generations, with the sturdy folk who under the stress of these times are seeking to establish a new order!

The answer to this question is indicated in a beautiful and impressive introductory paragraph found in Cotton Mather’s Magnalia Christi Americana, a most interesting record of the great events of the Colonial period as Mather saw them. In the second volume of this great work, bearing the title “Sal Gentium” we have a biographical sketch of the Rev. Samuel Danforth, the second son of Nicholas, who became famous as minister, scholar, poet, astronomer, – one of the earliest graduates and one of the first fellows of Harvard College, and the progenitor of illustrious descendants. In this paragraph Cotton Mather says, referring to Nicholas Danforth, that he was “A gentleman of such estate and repute in the world, that it cost him a considerable sum to escape the knighthood which K. Charles I imposed on all of so much per annum; and of such figure and esteem in the church, that he procured that famous lecture at Framlingham in Suffolk, where he had a fine mannour; which lecture was kept by Mr. Burroughs, and many other noted ministers in their turns; to whom, and especially to Mr. Shepard, he prov’d a Gaius, and then especially when the Laudian fury scorched them. This person had three sons, whereof the second was our Samuel, born in September in the year 1626, and by the desire of his mother, who died three years after his birth, earnestly dedicated unto the schools of the prophets. His father brought him to New England in the year 1634 and at his death, about four years after his arrival here, he committed this hopeful son of many cares and prayers, unto the paternal oversight of Mr. Shepard, who proved a kind patron unto him”.

“Famous Lecture”, “Mr. Shepard”, “Gaius”, “Laudian fury”. What colours do these words give to the picture we would visualize of Mr. Danforth. In Green’s “History of England”, and also in Samuel E. Morison’s “The Builders of the Bay Colony” we have references to the “lectures” in the Puritan era. William Laud as Bishop of London and later as Archbishop of Canterbury suppressed these “lectures” in so far as he could. They plainly were, to quote a modern word, “propaganda”, provided for out of private sources in the interest of the Puritan thought. The man who procured such a “lecture” must have been an outstanding Puritan leader of his town or possibly of a number of near-by towns and villages. May also refers to this term “lecture”, stating that it was given sometimes in the parish church in case of a sympathetic rector, otherwise elsewhere.

I have not yet learned the identity of this Mr. Burroughs referred to in this passage. Possibly he was one of the Puritan emigrants, but I have not found his name in this connection, and think probably he was a Puritan leader who remained in England. But there can be no doubt as to Mr. Shepard. He was the Rev. Thomas Shepard, the pastor described by Morison as possibly not the most learned of the New England clergymen, but “the most loved”. In 1634 he was living in retirement in Ipswich, only 15 miles distant from Framlingham. He was shipwrecked in his first attempt to leave East Anglia, but a year later in 1635 he came over with a number of personal followers in the Defence. He was at once welcomed in New Towne and organized a church, succeeding the Rev. Thomas Hooker, as he was leaving over the Connecticut Path to found the more distant settlement of Hartford. And this Mr. Shepard became, therefore, the pastor of Danforth in his new settlement.

And what was this “Laudian fury” referred to so vividly by Cotton Mather in this passage? Let me tell you in the words of Thomas Shepard himself as we find them in his autobiography published from the original manuscript about one hundred years ago. I quote his words:

“Dec. 16, 1630, I was inhibited from preaching in the Diocese of London by Dr. Laud, Bishop of that Diocese. As soon as I came in the morning about 8 of the clock, falling into a fit of rage he asked me what degree I had taken in the University. I answered, I was Master of Arts. He asked me of what College? I answered of Emanuel. He asked me how long I had lived in his Diocese? I answered 3 years and upwards. He asked who maintained me all this while, charging me to deal plainly with him, adding withal that he had been more cheated and equivocated with by some of my malignant faction than ever man was by Jesuit. At the speaking of which words he looked as though blood would have gushed out of his face, and did shake as if he had been haunted with an ague fit, – to my apprehension, by reason of his extreme malice and secret venome. I desired him to excuse me. He fell then to threaten me and withal to bitter railing, calling me all to nought, saying – `You prating coxcomb, do you think au the learning is in your brain?’ He pronounced his sentence thus. I charge you that you neither preach, read, marry, bury, or exercise any ministerial functions in any part of my Diocese; for if you do, and I hear of it, I’ll be upon your back and follow you wherever you go, in any part of this kingdom, and so everlastingly disenable you. I besought him not to deal so in behalf of a poore town, – here he stopt me in what I was going to say, – `a poor town! You have made a company of seditious factious bedlams. And what do you prate to me of a poor town?’ I prayed him to suffer me to catechise on the Sabath days, in the afternoon. He replied, `spare your breath, 1’11 have no such fellows prate in my Diocese. Get you gone! And make your complaints to whom you will’. So away I went – and blessed be God that I may go to HIM”.

I think we can agree that this was a scorching blast.

And now what does Mather mean by saying that Danforth proved a “Gaius” to these lectures and especially to Mr. Shepard? The reference in the use of this name “Gaius” which had occurred to me as a lawyer was to the famous writer of the Romans, who left his Institutes as one of the sources of Roman law. If so, then I thought Mather would have us believe that Danforth, although a layman, in some unusual way was a counsellor to these “silenced” Puritan clergymen. This seemed appropriate, especially in the case of Mr. Shepard when we realize that in 1634-5, as he was in hiding in Ipswich and on his way hither, he was only 29 or 30 years old, while Danforth was almost a score of years his senior. From this point of view we would see Danforth as the counsellor and guide of Shepard and as such a strong support in the Puritan settlement of New Towne.

But a message has been received from Canon H. C. 0. Lanchester, Rector of Framlingham, who, as a clergyman, has promptly recognized the connection in which this name is used. This message which has come from him is to “see Romans 16 verse 23”6. This begins with these significant words, “Gaius mine host”. Mather clearly had in mind the man “Gaius” thus immortalized in Paul’s Epistle, as a gracious host who had befriended him and wished to be joined in the salutation “to all that be in Rome, beloved of God, called to be saints”.

What a happy solution of this mystifying reference! And what a beautiful tribute to this older Danforth, as we recall the days of the trials of the Puritan clergy in old England.

Danforth at once became a leading citizen as proved by our own Colonial records. He was a selectman during the years 1635-6-7 and a Deputy of the General Court for 1636-7. He was appointed one of three commissioners to set the bounds of the New Plantation on the Charles River and also to determine the bounds between nearby places, particularly Dorchester and Dedham. He was selected as one of eleven men who were given the sole power of selling at retail “strong water”, an effort thus early to place the troublesome question of the sale of intoxicating liquors in the hands of the leading citizens. And what is particularly interesting, he was one of the committee headed by Governor Winthrop “to take order for” the new college, and this before the name Harvard was associated with it. After only four years in his new home he died in April, 1638. While his name has been obscured by the greater public records made by his sons, Thomas, Samuel and Jonathan, still in these four years there is enough, it seems to me, to entitle him to remembrance as a strong man, an influential leader, and undoubtedly a determined Puritan.

“A determined Puritan” indeed! The interesting ideas which issue from this story concern not just the history of New England, but our history locally in Framlingham. What micht have persuaded Nicholas not to emigrate? Booth informs us that he was a churchwarden in 16227. Was he content that the reformed way of being a Church was comfortable and in line with his own way of thinking? We need to remember that this was a peculiar period for the Church of England in Framlingham. The living was held at this time by Thomas Dove, who was appointed rector at the age of 28/29 in 1584. Dove was called to higher things, being made Bishop of Peterborough in 1601. He held Framlingham in plurality, leaving his curates to run it almost entirely. After one called Moore, Richard Golty became curate in 1624, and then when Dove died in 1630, he began his first spell as Rector.

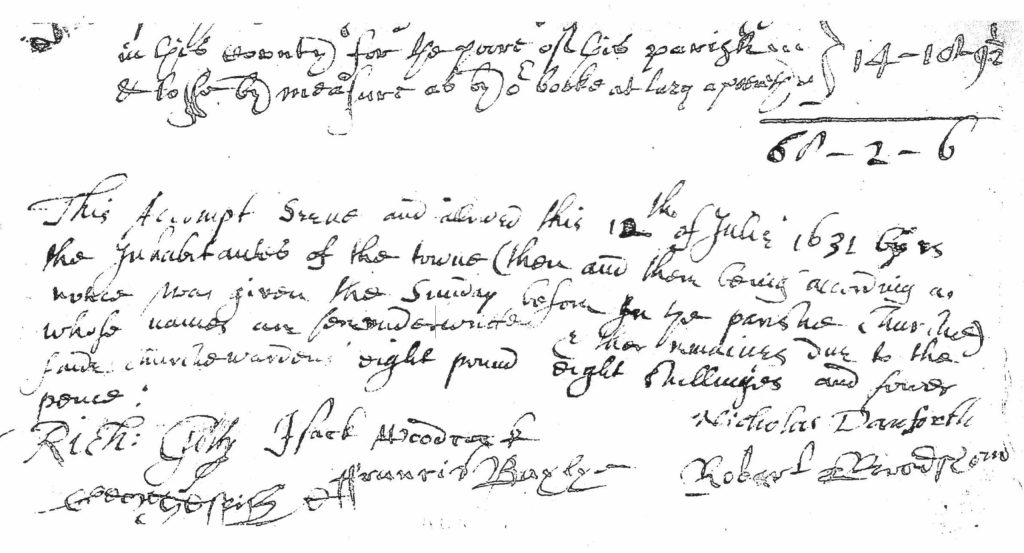

Copies of the Churchwardens’ Accounts in the Suffolk Records Office indicate that, as late as 1631, Nicholas and Golty worked together as parish officials. But was Golty’s churchmanship something that Nicholas was not really comfortable with? Or was it the national trend, with high church Laudism coming back into vogue, that was the issue for Nicholas? His associates, the Revds. Symmeses, his father-in-law, and brother-in-law, the Revd. Thomas Shepard and the mysterious Mr. Brroughs were clearly also of a “determined Puritan” persuasion8.

Was the appointment of Golty a kind of last straw which enabled Nicholas to make his mind up? How much pressure did the other clergy exert upon him? Allied to all this would be the fact that Archbishop Laud, who had hounded them so much, was translated from Bishop of London to be Archbishop of Canterbury in 1633. Therein perhaps lie answers to the question posed by John Merriam, “what was there in 1634 to induce Nicholas Danforth… ?”9.

Nicholas, who knew just four (very active) years in New England, dying in 1638, did not, of course, live to hear of a Puritan clergyman being appointed to St. Michael’s as happened in 1650. During the period of the Commonwealth, Dr. Henry Sampson (a Pembroke College man, fitting the requirements of Sir Robert Hitcham’s will) assumed the living. His tenure, however, was no more than that of the Commonwealth. With the Restoration, Golty came back for sixteen and a half more years, a “vicar of Bray” experience10. Sampson then became one of the first non-conformist ministers in Framlingham’s religious history. The story of this has well been told by the Revd. Clifford Reed in earlier issues of this journal11.

America will say that by this time the focus of both Puritan and Danforth influence had clearly moved to be with them. In the career of Thomas Shepard, a plaque to whom may be seen on the railings outside the precincts of Harvard University, is one sequel to this story. But more relevantly to us, the Danforths established a dynasty (and a location) of which New England is proud, and to which this town of Framlingham can feel it made a considerable contribution. What we have considered suggests that Nicholas did clearly move predominantly for religious reasons. If, however, some thought did go through his mind that there were pioneering opportunities for his children, he was also very right. The contribution of the Danforths, born and partly raised on Framlingham soil, has been, both to the religious and to the secular life of America, a considerable one.

Addendum

There is another link between seventeenth-century Framlingham and New England. In February of this year we stayed with the Revd. Richard Willcock and Vivienne in the delightful cottage which they have in Cumbria. Many will remember Richard as the Rector of Framlingham 1992-2003, and a former president of the Framlingham and District Local History and Preservation Society.

Richard has been researching the story of Elijah Corlett. Records in Pembroke College (where Richard did a spell as Acting Chaplain) indicate that Corlett was a schoolmaster in Framlingham before he became another of the Puritan emigrants to New England. J. and J. Venn’s Alumni Cantabrigienses record him as follows12:

Corlett Elijah 8. A. 1634 (Incorp from Oxford). S. of Henry of London. Wax chandler. Exhibitioner from Christ’s Hospital, M.A. from PEMBROKE, 1638. Ord. deacon (Norwich) Sept. 1633. For a time schoolmaster in Framlingham, Suffolk. Afterwards Master of Halstead Grammar School, Essex, 1636. Emigrated to New England. Master of the school at Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1641-87. Died Feb. 25, 1666-7.

Cotton Mather, the notable historian of New England Puritan history, refers to the key part that Corlett played in preparing students for Harvard College. Although he was ordained, he clearly preferred the role of teacher. Mather notes that he had a determined policy that native Americans (particularly the sons of chiefs) should also have the opportunity to lean and enter Harvard13.

This autograph is the only one known for Nicholas Danforth in the UK (there may be others in the USA).

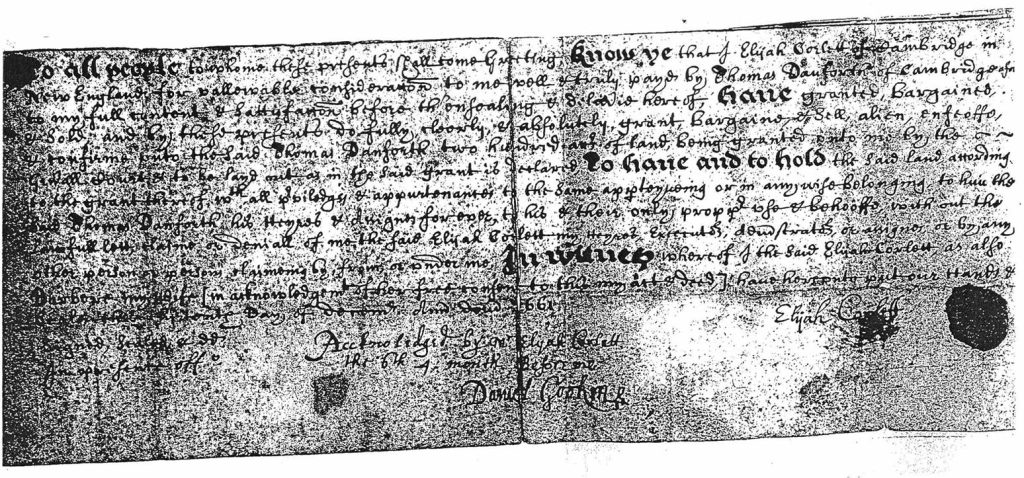

One consequence of this seems to be that he came into possession of two hundred acres of new land in the region of present-day Framingham. Copies exist of the deed of conveyance of this land to Thomas Danforth, so that it joined the considerable other pieces of land that he had acquired to become the Danforth farms or the Framingham Plantation14.12 Thus Framlingham has another direct link with its New England near namesake. We can well imagine that they would have exchanged reminiscences of Framlingham when they met in Massachusetts.

Cotton Mather makes special mention of Corlett’s contribution to his personal development. Mather had a stammer which he thought would prevent him from being a minister of religion. His studies were tending towards a career “in physic”. Corlett taught him to speak slowly, citing that no-one stammered when singing. A cure was effected and so Mather pursued a career in the Church.

As regards the story of Framlingham, this information throws light on two areas of interest. Firstly it helps to reinforce our knowledge of schooling in Framlingham prior to Sir Robert Hitcham’s will. Richard Green mentions the school in the Guildhall in the Market Place circa 1564-163215. Surely this must have been the school of which Corlett was the schoolmaster? What brought him to Framlin9ham? Did he meet Richard Golty, the Rector at Pembroke where they had both been students, albeit not at the same time? Did Golty persuade him to come briefly to Framlingham?

In his research Richard Willcock has consulted with Jane Ringrose, the archivist at Pembroke College. She presents the proposition that the whole Hitcham/Pembroke/Framlingham link may have grown out of the relationship which these students had with their old college. Hitcham, as is prominently known, was a proud Pembroke alumnus from the days of Elizabeth 1, and he not only made the college the premier trustees of his will, but became a significant benefactor. Hitcham’s decision to purchase the castle may have had much to do with the fact that he was living back in Suffolk, and saw the opportunity to buy the castle as a good use of his considerable wealth. But the nature of the provisions of his will, with direction to create a new school, could well have been to do with prompting from Golty, the incumbent. In the event, as is well known, the controversy over the will postponed the school’s opening until 1654. By then Corlett was well settled in New England and the trustees of the will looked to Zaccheus Leverland (another of Framlingham’s keen historians) a clerk in the Herald’s Office in London, to come as the first master of the new school16.

Footnotes

[Editor’s interpolations enclosed in square brackets].

- FRAM Journal, Series 5 No 6, April 2007 ↩︎

- Library of Congress, “Danforth genealogy. Nicholas Danforth, of Framlingham, England, and Cambridge, N. E. [1589-1638] and William Danforth, of Newbury, Mass. [1640-1721] and their descendants”, https://www.loc.gov/item/03005660/ ↩︎

- J. Merriam I. The Contribution of Framlingham Suffolk, England to the Colony of Massachusetts Bay (1930); (and) Framingham to Framlingham: a greeting across the sea in memory Of Nicholas Danforth and his descendants (1931). ↩︎

- John Booth (1886-1965) was one of the most notable Framlingham historians of the twentieth century. His publications include Nicholas Danforth and his neighbours (1935)., (and) The Home Of Nicholas Dar[forth in Framlingham Suffolk, in 1635 (1954). (Booth met Merriam when the latter came to the Framlingham Pageant of 1931. They clearly worked together on the stories. As noted above (page 7) Merriam contributed an introduction to Nicholas Danforth and his neighbours, and also to Booth’s The Home of Nicholas Danforth …). [The latter was reprinted in this journal 5th series no. 3 April 2006 pp. 4-12]. ↩︎

- [Booth, Nicholas Danfiorth … op. cit. pp. 6-10]. ↩︎

- See also Acts 20:4, 1 Cor 1:14, 3 John 1: 1-11. [Margin note by T. Guilder]. ↩︎

- [Booth, The Home… op. cjt.]. ↩︎

- [Booth, Nicholas Danforth … op. cit. p. 10]. ↩︎

- [Referred to ibid. p. 7]. ↩︎

- [For a detailed account of Richard Golty’s chequered career, see A. Goulty, “Richard Golty, Rector of Framlingham 1630 to 1650, and 1660 to 1678” in Fram: the jourmaI of the Framlingham and District LocaI History and Preservation Society, 3rd series, no. 10 (August 2000) pp. 20- 28]. ↩︎

- [C. Reed, “Dissent into Unitarianism: origins, history and personalities of the Framlingham Meeting House and its congregation” in Fram, op. cit., 4th series, no. 5 (December 2002) pp. 5-14; 4th series, no. 6 (April 2003) pp. 23-33]. ↩︎

- [J. and J. Venn, Alumni Cantabrigiensis … (1992) vol. 1 part 1]. ↩︎

- [C. Mather, Magnalia Christi Americana … (1702) see pp. 6-9 above]. ↩︎

- [The photocopy currently (2007) on display at Lanman Museum is reproduced above]. ↩︎

- [R. Green, The History, topography, and antiquities of Framlingham and Saxsted … (1834) p. 187]. ↩︎

- [Ibid p. 14]. ↩︎